by Clone Wen <cw4295@nyu.edu>

The Korean Cultural Center New York at 32nd Street presents Nam June Paik: The Communicator from September 26, 2025, to November 22, 2025. The exhibition surveys Paik’s cross-media practice, linking television, video, installation, and performances. It features Main Channel Matrix (1993 to 1996) with 65 monitors, the transparent housing TV Cello (2002), Living Egg Grows (1994), and Rehabilitation of Genghis Khan (1993), shown alongside archival photographs and drawings from the 1980s to 2000s.

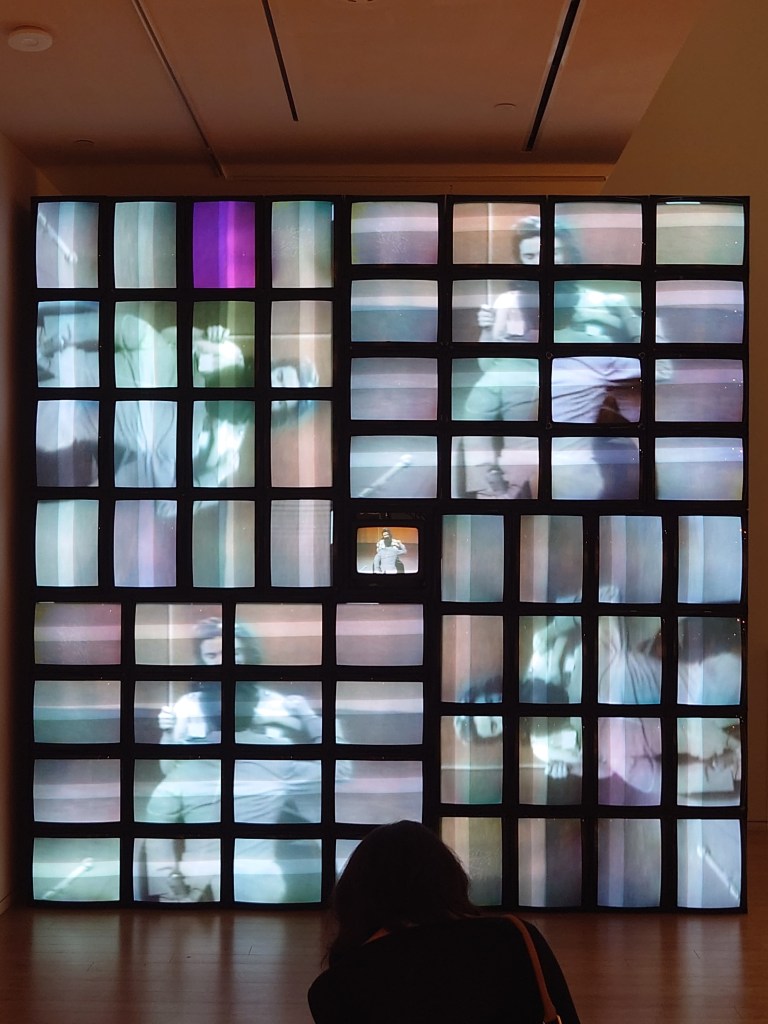

The largest installation on site is Main Channel Matrix (1993 to 1996). It uses a matrix computer and 65 monitors to form a huge television wall that enlarges a single center CRT television into a movie palace-sized screen. The magnification and television flicker produce strong vertigo, recalling the room of monitors where Neo meets the Architect at the end of the Matrix trilogy. Yet, this video installation predates the first Matrix film, released in 1999, by several years. In terms of content, the giant screen carries segments of performance and experimental image making, including a traditional Buchaechum Korean fan dance, a performance piece by John Cage, and the Human Cello performance from 1965, where Charlotte Moorman bows Nam June Paik’s body.

Two other large installations, Rehabilitation of Genghis Khan (1993) and Living Egg Grows (1994), develop the metaphor that video becomes the heart of sculpture and television becomes the embryo of sculpture. Living Egg Grows here uses 8 Samsung televisions and 3 glowing egg lamps to make the image of a fetus or an egg appear to grow inside the screens. Rehabilitation of Genghis Khan (1993) presents a diver helmet figure with a nomadic electronic body composed of screens, pipes, cables, and mechanical parts, with a monitor set in the chest as a heart. That heart appears as a flicker film, overlaying geometric and simple figures such as a flower, fish, and bottle. Some other times it twists the opening color bars or test patterns, and reaches a switching density that feels like 10 images in one second.

It is notable that Paik’s sculptures present screens that are primarily front facing. Looking from the side and the back, you may see their cyberpunk body has wastepunk backsides. The front is an iconic Genghis Khan with a video heart, while the back reveals wiring and sockets. Likewise, TV Cello (2002) dissect itself with a transparent case of visible cathode ray tubes, circuits, and fans. The other series of composers and historical personae, such as Charlie Chaplin and Yulgok, builds figures whose backsides show vintage radios routed through new power strips inside wooden cases. Furthermore, Behind Main Channel Matrix (1993), the tangle of cabling is accompanied by a repair chair. The fact that a person may sit behind 65 monitors signals the time and effort required to service and restore the work.

In a way, the heart of Nam June Paik’s video installations is no longer the same set of monitors as in 1993, just as the replaceable duct-taped banana in Maurizio Cattelan’s 2019 artwork Comedian. Like film, video installations pass through cycles of digitization and restoration. The lingering question is how to grant performance and video a durable afterlife. One answer is making television shells heart of the humanoid sculpture or the matrix. In doing so, the cathode ray tube can outlast its era and enter art history for over 30 years. By linking performance, video, installation, sculpture, and archive into a single media cycle, Paik secures an enduring legacy of his avant-garde practices.