The Potential Contributions Of Artificial Intelligence And Computational Tools To Film Historiography And Media Obsolescence/Excess

Open-ended reflections by Marina Hassapopoulou

A very recent example to begin the conversation on the potential contributions of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools to issues of scale, nontheatrical media abundance, and the endless remixing of archives is the AI-generated short video Swim (Eryk Salvaggio, 2024).

Swim constructs a compelling audiovisualization of the fusion of new technologies, artistic vision, cultural memory, and archival remix.[1] Salvaggio used generative AI (e.g., Stable Diffusion) to “dive” into The Prelinger Archive (via the Internet Archive) for public domain material he could place in conversation with AI systems to reflect on the “datafication of memory” and to (re)contextualize often-anonymized AI training data–in this case, the short Underwater Ballet reel from 1952, featuring erotic underwater swimming.[2] Swim is part of a series of AI-generated process-oriented works that reverse engineer the typical results-focused and context collapsing properties–not to mention questionable intellectual property ethics[3]–of typical AI training data. Salvaggio’s use of public archives to demystify the underlying ethical and cultural issues at stake in AI training additionally functions as a type of archival remix that shifts the focus back on the original materials. In this case, the AI archival remix spotlights forgotten yet accessible archival gems, rather than rendering archival data anonymous and interchangeable within a potentially infinite and nondescript AI online database.

Although some of the tools and approaches are different, this objective of re-engaging with archives is similar to forward-thinking cultural institutions such as the EYE Filmmuseum’s incorporation of new tools and user-oriented practices to increase public engagement with collections. Some older examples include the Scene Machine found footage remixing tool (2012+), and the EYE’s Celluloid Remix contest (2009-2012) that encouraged aspiring filmmakers to remix digitized film fragments from the museum’s collections (for the 2009 contest, for instance, the collection included public domain orphan amateur footage short in the Netherlands between the 1920s-30s).[4] Following suit, the New York Public Library’s digitized collections have been available for online public access and remixing using various digital humanities tools (and even included a stereoscopic filter).[5]

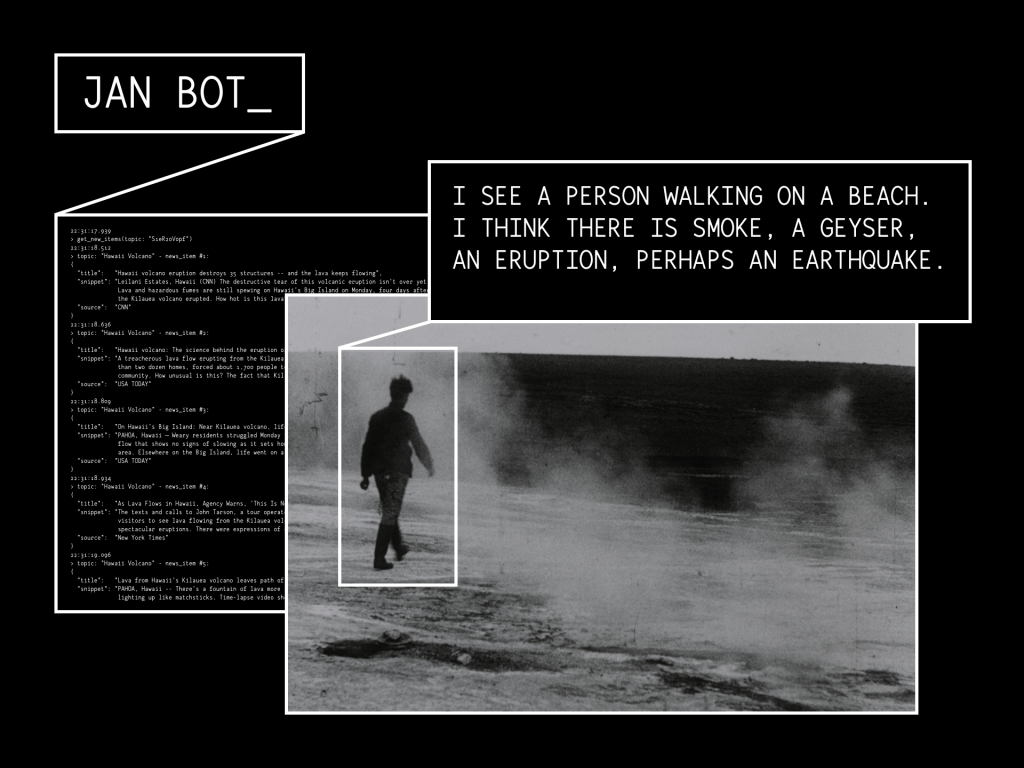

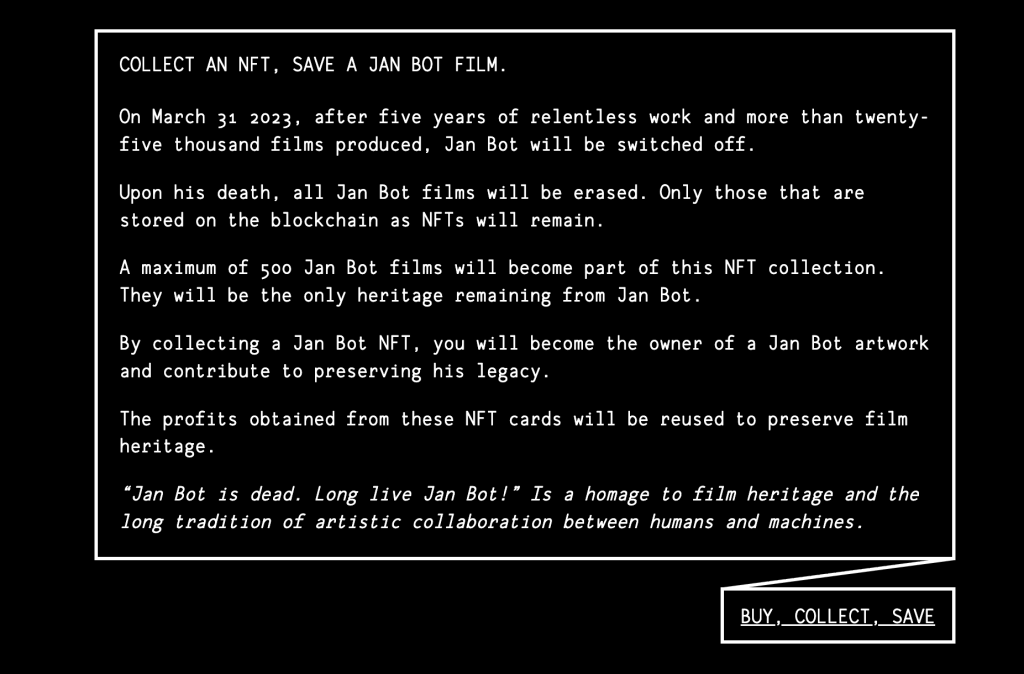

An even more relevant example to AI remix is the EYE’s natural language processing AI, Jan Bot (2017-2023). For almost 6 years, Jan Bot generated its own audiovisual media in real time by combining popular topics from Google Trends with found footage from the EYE’s Bits & Pieces found footage collection. Jan Bot is a perfect example of how AI can be used to re-imagine how neglected aspects of the cinematic cultural past can acquire new relevance when repurposed within newer contexts. One of Jan Bot’s creators, Pablo Núñez Palma, describes the Jan Bot experience as follows: “we see through an old film archive through the eyes of a new technology and, in doing this, we experience machine intelligence as it really is.”[6] Grazia Ingravalle’s new book, Archival Film Curatorship: Early and Silent Cinema from Analog to Digital (2023), is more critical of Jan Bot and other digital remix platforms’ overall archival and curatorial contributions, arguing that their “remixes often stop short of performing the task of historical mediation at the core of historiographic and curatorial work” (91). Yet, the undeniable engagement that the online public has had with Jan Bot, even if just for the sheer novelty of its algorithmic tactics and for the subsequent blockchain NFT marketability of its filmic products, has indicated a new peak in both automated (AI-driven) and online (human) interaction with the Bits & Pieces collection.

In 2023, the creators of Jan Bot decided it was time for its death since it no longer served the epistemological purpose of rediscovering cinema and culture through a (once) emerging technology. During its short life span, Jan Bot generated more than 25,000 unique videos. In grappling with the scale of Jan Bot’s production, the creators decided to use newer rather than older methods (e.g., hard drive, or even web recordings) to archive the videos. So, they decided to invite Jan Bot’s audience to preserve its films through NFTs. Jan Bot’s creators see NFTs as “a way to archive media files in decentralized servers” and thus appropriately preserve the legacy of future-forward Jan Bot in a new medium. Although traditional archivists would argue that NFT archiving does not actually preserve the original in its authentic form, in this case, I’m not sure if this question is central to Jan Bot’s nature (though it certainly is relevant in discussions of the preservation of other archival materials). NFTs contain a copy of the original work that can be legally used as a digital backup and cannot be copied–it can only gifted, shared, and purchased. Núñez-Palma insightfully argues that,

NFTs can be an effective way to fulfil the archival need to store media files in non-monopolized servers, because they are secured in a public blockchain. Even if the original media file is–due to its large size compared to the blockchain standards–not feasible to be directly attached, the NFT will include a permalink to it. And because regular hosting servers are centralized and often depend on subscriptions that if not maintained can lead to broken links, media files are being hosted using peer-to-peer protocols, such as IPFS (Interplanetary File System) or Filecoin. [7]

Through there are currently many unknowns, the concept of using NFTs on public blockchain as “compressed” archives (or archival stand-ins) might be a promising way of addressing issues of scale and to creating new forms of decentralized and user-generated meta-archives. AI as a research tool and archival aide is a relatively new territory, and I only mentioned a few different case studies to consider its potential affordances–which has been a welcomed shift from usually focusing on AI’s legal and ethical issues.[8] AI scholarship is currently one of the trendiest topics in academia, and interest in AI is spreading into archival and cultural studies. Instead of an impossible conclusion, I would like to stimulate more inquiry by referencing just a handful of the many promising publications relevant to the Orphan Film Symposium’s and this workshop’s interests, in addition to the works already cited in the footnotes. What are your thoughts on the contributions of AI to historiography and cultural archives? Comment below.

- ACM Journal of Computer Cultural Heritage special issue (Jan. 2024): “Applying Innovative Technologies to Digitised and Born-Digital Archives” and the Aeolian Network, https://www.aeolian-network.net/outcomes/.

- AI & Society special issue (2024): “When Data Turns into Archives: Making Digital Records More Accessible with AI,” and the accompanying LUSTRE project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in the UK. LUSTRE connects policy makers with digital humanists, computer scientists and GLAM sector professionals (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) https://lustre-network.net/ .

- Other recent AHRC-funded projects include:

- LUSTRE (Unlocking our Digital Past with AI), in partnership with the Cabinet Office

- EyCon (Visual AI and Early Conflict Photography) in partnership with French researchers

- AEOLIAN (UK/ US: AI for Cultural Organizations)

- ExpressiveAI.net’s recent News & Events blog, Opinion Pieces, and AI Pedagogy pages for latest updates

Piece originally prepared for an invited participation at the Orphan Film Symposium seminar “Considering Questions of Scale in Non-Theatrical Film,” organized by Tanya Goldman and Martin Johnson, NYU, April 2024.

[1] Watch Swim and explore Salvaggio’s theory-practice here: https://www.cyberneticforests.com/news/swim-2024 . For a particularly useful post on archives and historiography in the era of AI, see: https://www.cyberneticforests.com/news/social-diffusion-amp-the-seance-of-the-digital-archive . Salvaggio is one of the artists featured on ExpressiveAI.net.

[2] Watch Underwater Ballet on the Chicago Film Archives website: https://collections.chicagofilmarchives.org/Detail/objects/6632

[3] This brings up a whole other equally important topic that is outside the scope of this brief overview. Some very recent articles that tackle the grey areas of AI copyright and issues of scale through copyright infringement include: Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz’s “The Work of Copyright Law in the Age of Generative AI” and Noam M. Elcott and Amy Alder’s “Art Beyond Copyright” for the Grey Room’s special dossier on Art and Law(2024).

[4] Celluloid Remix. https://celluloidremix.openbeelden.nl/ .Unfortunately, not all submissions have been archived online, though the 2012 iteration of the contest is better documented than the 2009 one.

[5] The NYPL Share & Reuse resource: https://www.nypl.org/research/collections/digital-collections/public-domain

[6] “Jan Bot,” Docubase, accessed June 24, 2022, https://docubase.mit.edu/project/jan-bot .

[7] Pablo Núñez Palma, “Who, why and how was killed Jan Bot,” Medium.com 2023 https://medium.com/janbot/who-why-and-how-was-killed-jan-bot-b79b9bf94787 .

[8] For a complex discussion of AI through the lens of interactive media, see Hassapopoulou’s Interactive Cinema: The Ambiguous Ethics of Media Participation (University of Minnesota Press, 2024).

Leave a comment